For a few weeks in August, the hoped-for soft landing of the U.S. economy seemed more likely than not. In the decades since the Federal Reserve Bank embraced the dual mandate of low inflation and full employment, the central bank has tried, without success, to battle periods of inflation deftly enough to avoid tipping the economy into recession. After likely waiting too long to raise rates, the Fed was aggressive from March through July, and the data from mid-year showed a significant slowing in the rate of inflation from June to July. Perhaps, it was hoped, August would show further disinflation, allowing the Fed to keep rates from becoming restrictive.

What transpired instead was an unexpected increase in both the consumer price index and core inflation in August. At the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) meeting on September 20, a 75-basis point hike was announced, bringing the Fed Funds rate to 3.0 to 3.25 percent, a level above what was considered neutral to the economy.

Of greater significance than the rate hike itself were the comments and forecasts of Fed Chair Jerome Powell and the 19 members of the FOMC. Powell reiterated the central bank’s resolve to bring inflation back to its two percent long-term level and betrayed his belief that that effort would cause a recession in 2023. While that position was consistent with what Powell had been saying openly all summer, the forecasts of the 19 committee members seemed to shake the markets.

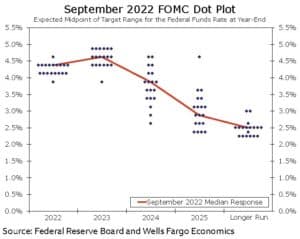

Members of the FOMC release their expectations for the Fed Funds rate at the end of each meeting. The dot plot of those expectations is usually a blueprint for rates in the coming quarters. Only one of the 19 members forecasted the Fed Funds rate to be below four percent when 2022 ends. All but one member forecasted the rate to be below 4.25 percent through 2023, with 12 of the 19 expecting the Fed Funds rate to exceed 4.5 percent. These same FOMC members expressed almost no expectation of rate increases in 2022, so the dot plot is not an accurate forecast beyond the next meeting or two; however, the strong consensus around the four-plus percent rate at the start of 2023 ensures that rates will go at least one percent higher after the November and December meetings have concluded.

The higher interest rate environment has had a chilling effect on commercial real estate, but the Fed’s actions have greater significance to the overall economy.

Leaving aside the debate about whether the central bank took inflation seriously enough, soon enough, the problem facing policy makers lies in the Jekyll-and-Hyde economy. Hiking rates by 400 basis points during the last three quarters of a year should bring the economy to a screeching halt, yet six months and 300 basis points into a tightening cycle, that is not the case. While the Commerce Department confirmed the 0.6 percent decline in gross domestic product (GDP) in the second quarter – marking two consecutive quarters of decline – many of the metrics of the economy are healthy.

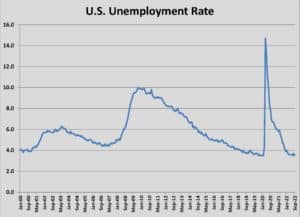

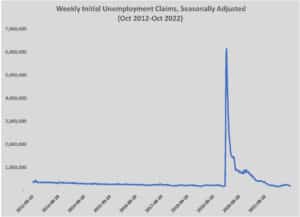

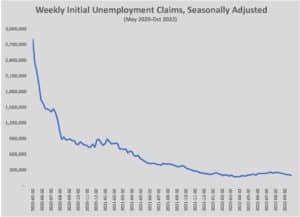

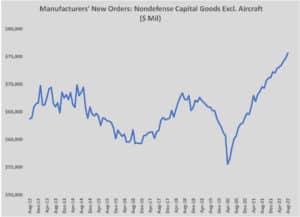

Unemployment remains unusually low, falling back to the pre-pandemic rate of 3.5 percent in September. Initial unemployment claims have fallen below 200,000 per week again. Continuing claims fell below 1.4 million, nearly 20 percent below the low for the pre-pandemic business cycle. Job creation was slower in September, but the 265,000 new jobs exceeded the consensus forecast for the month. Job openings fell by 1.1 million in August, but there are 5.1 million more unfilled openings than there are unemployed persons. Consumers are expressing their fears about the economy while spending at record levels, all while prices have been depressing their buying power. Consumer sentiment rose in August to a reading of 108. Factory orders for non-defense capital goods surged by 1.6 percent from July to August to $75.6 billion, surprising economists. The increase is evidence that businesses are continuing to invest in equipment, despite higher borrowing costs.

|

|

The housing market is an excellent example of the difficulty in measuring the effect of tighter policy. Housing is one of the first sectors to be hurt when monetary or fiscal policy becomes restrictive. And, so far this year, that has been the case. The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate was 6.7 percent at the end of September, more than 120 percent higher than one year before. Housing starts were off by nine percent year-over-year in August but have declined more steeply for the full year. New home sales rebounded by almost 29 percent in August – driven by a short-lived drop in mortgage rates – but are on pace for a 15 percent decline for the year. Existing home sales are off 19.9 percent year-over-year; however, the median home price was 7.7 percent higher than August 2021. While that level of home price appreciation was shrinking compared to earlier in 2022, the fundamental imbalance of supply to demand is unlikely to cause prices to plummet. In August, there were still 2.5 offers for each home sold.

This strange divergence in cause and effect from raising interest rates is evidence that the inflationary cycle is as much a product of supply not recovering from the pandemic as quickly as demand as it is a result of loose fiscal and monetary policy. Pandemic relief put trillions of dollars into the pockets of consumers and businesses, but prices remain stubbornly high well after those relief funds have been spent, even in the face of steep increases in the cost of borrowing. It is more likely that prices will begin to fall before the Fed can avoid a recession, but the upward pressure on rates will continue until unemployment rises above four percent.

Aside from the impact on the housing market, recession will slow commercial real estate more than other sectors. A downturn will be felt differently from one property type to another.

The office market is the largest commercial real estate subcategory. As a property type, office buildings have been under severe pressure since the pandemic disrupted the workplace. While a recession will likely decrease office employment, it is also likely to increase pressure on workers to return to the office. That may push occupancy levels high enough to halt the rising vacancy rates. Office vacancy rose to 12.5 percent in the third quarter.

Hospitality has rebounded smartly from its pandemic lows, with occupancy levels roughly equal to the same as October 2019. Average daily rate and revenue per average room are up by more than 15 percent year-over-year. Inflated travel costs and corporate cost-cutting will cool demand in 2023, likely offsetting the favorable conditions for foreign visitors to the U.S. Lending for new hotels and travel destinations is still tentative.

Retail properties were also devastated early in the pandemic, a tough blow to a property type already reeling from the impact of online shopping. Once vaccines were widely available, however, retail traffic surged, and retail properties have prospered since. Vacancy in retail is just above four percent and rents for retail have increased 4.4 percent year-over-year. Construction has not kept pace with demand, helping to absorb inventory. The outlook for retail is slightly negative, assuming that persistent inflation begins to be a drag on consumer spending in 2023.

Industrial properties remain the strongest commercial real estate category. Vacancy remains below four percent, an all-time low. Amazon’s announced pullback on new construction will help keep net absorption positive and rents increasing. Construction demand will be supported by increased re-shoring of the supply chain and long-term growth of e-commerce.

The other winner of the pandemic economy was the apartment sector, particularly in desirable markets outside the major (expensive) gateway cities. Higher mortgage rates have been a disincentive for homeowners to sell their homes, even as household formation grew. Financing and investor demand for apartments has facilitated a surge in construction, which has finally cooled rent growth. Vacancy rates are still at historically low levels but have gone higher for four consecutive quarters.

The most telling trend in the apartment market is the slowdown in net absorption. The quarterly average for 2022 has been 72 million square feet of net positive absorption, a rate that has been slowing as the year progresses. That compares to an average of 175 million square feet per quarter in 2021. Permits for multi-family units fell in August, to 571,000 units, but will need to fall well below 500,000 units to stop the downward trend in absorption.

The slowdown in commercial development has shown up in the construction data since June. Spending on commercial construction has been flat, at an annualized $112 billion, even though inflation has pushed higher by roughly two percent each month. The same has been true of construction spending overall. For August, the most recent month reported, overall spending fell only $8 billion compared to July. Construction spending is up 8.5 percent year-over-year, but that lags the 23 percent rate of inflation considerably. Only nine of the 39 sub-categories of public and private construction are negative year-over-year; however, only construction of manufacturing and water supply facilities have seen increases that outstrip inflation.

The outlook for U.S. construction in 2023 depends to some degree upon how much the economy slows, whether a recession is formally realized or not. There are bulwarks against much of a decline in construction spending. The steep decline in residential construction in 2022 will be a low basis from which 2023 will be measured and demand for new construction will be boosted by the tight inventory of existing homes for sale. Funding from the bipartisan infrastructure bill passed in 2022 will begin flowing through the state and local government to a higher degree in 2023. Interest rates should peak in the first quarter of 2023, so capital costs should be somewhat lower as the year goes on.

It will be the persistence of construction inflation and continued disruption of the supply chain that determines how much construction proceeds in 2023. While it seems inevitable that the Federal Reserve Bank aims to slow the economy to the point of recession, demand for construction has been pent up by higher costs and undependable availability for two years. Improvements in supply and/or relief from double-digit inflation could unleash pent up activity regardless of the strength of demand from the overall economy.