Year-end reporting of construction activity confirmed that 2021 was an unusually strong year for construction and development, despite headwinds from inflation, labor shortage, and uncertainty caused by the surging coronavirus. The combination of surging economic demand, high levels of cash reserves, and cheap capital turned an uncertain beginning into a great year for construction.

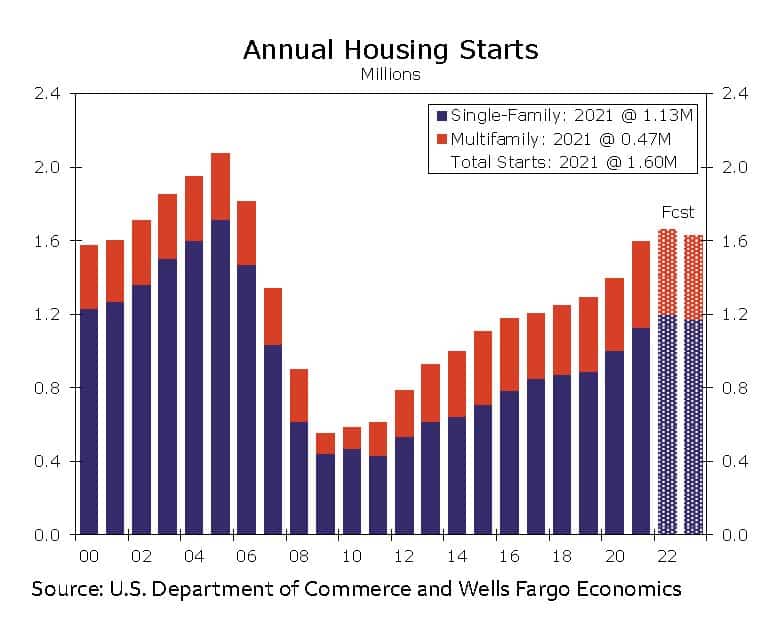

On the residential side of the industry, home builders began construction on 1,595,100 homes in 2021, with single-family starts totaling 1,123,100 units. That marks the best year for single-family starts since 2006, which – as we found out in 2008 – was driven by financial products rather than demand. Multifamily construction experienced the best year since 1987, jumping 21.3 percent to 472,000 units. Housing permits, which tend to lead starts by 30 to 90 days, increase by 17.2% in 2021 to 1.725 million.

Single-family permits rose 13.4 permits to 1.11 million, while multifamily permits spiked by almost 25 percent to 614,000 units. With permits rising faster than starts at the end of 2021, starts are likely to increase in 2022, despite slightly higher interest rates.

Construction spending overall also reached new highs in December. Total construction topped $1.6 trillion for the third consecutive month. While inflation pushed construction dollars higher, demand from private nonresidential investment recovered to mid-2019 levels by the middle of 2021.

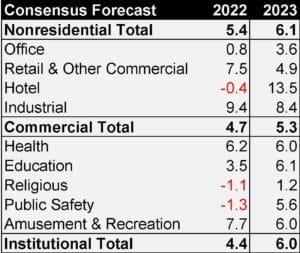

Looking ahead to 2022 and 2023, construction economists see the economic recovery extending from residential to nonresidential construction. After declining by five percent in 2021, nonresidential construction is expected to climb by 5.4 percent in 2022 and 6.1 percent in 2023, according to the American Institute of Architects’ (AIA) Consensus Construction Forecast. AIA convenes the economists from eight organizations focused on the construction industry, including FMI, Dodge Construction Network, Construct Connect, Moody’s Analytics, IHS Markit, and Markstein Advisors. The panel expects slight declines in only the hotel, religious, and public safety sectors. The largest increases are forecast in industrial, retail and other commercial, health, and amusement and recreation.

AIA’s chief economist, Kermit Baker, notes in the comments announcing the forecast that in 2021 architects registered the highest average score for the Architectural Billings Index since 2007. Revenue at AIA firms increased by six percent in 2021 and is expected to grow by seven percent in 2022. Billings are a leading indicator of activity 12 months in the future.

Ken Simonson, chief economist at the Associated General Contractors (AGC), sees the challenges to the construction market in the near- and medium-term coming from the supply side of the equation. Simonson acknowledges that demand could be diminished by pullbacks because of further virus outbreaks but cautions that the uncertainties in project costs and availability of materials present greater challenges to construction activity. He also warns that the pre-pandemic shortage of skilled workers and supervision has worsened.

As an illustration of the latter problem, Simonson notes that job openings in construction reached 350,000 at the end of 2021 an increase of more than 32 percent from a year earlier. Job openings for construction peaked at 300,000 in December 2018, arguably the height of the last business cycle.

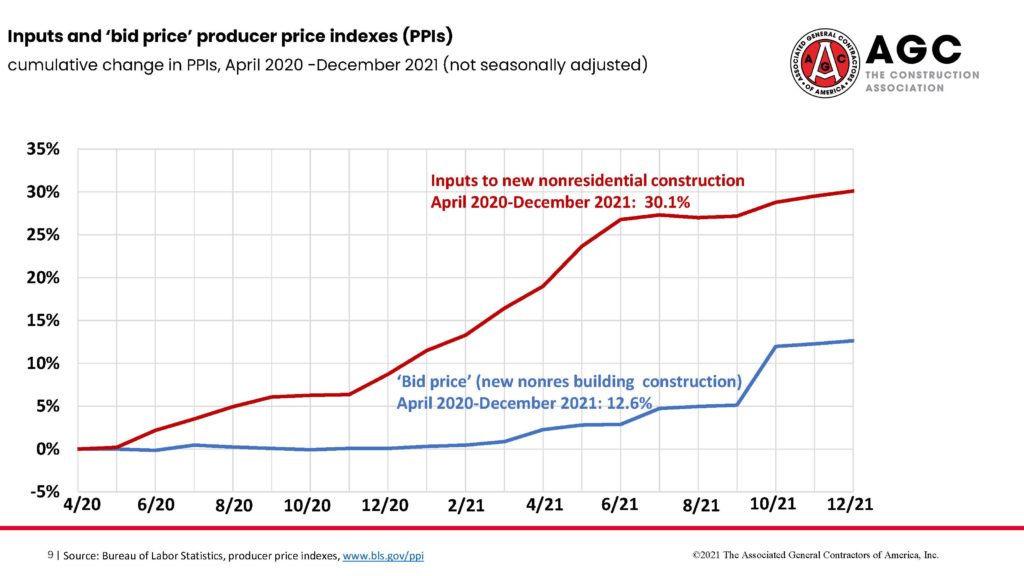

Simonson also warns that the impact of inflation is likely to continue through 2022. Citing the 18 percent gap between the input costs and the bid prices for nonresidential construction, Simonson notes that similar variances in the past have lasted two years or more. The two most recent prolonged variances, beginning in 2010 and 2017, each lasted two years. The current gap between costs and bids began in 2021.

The momentum of the U.S. economy makes it likelier that the impact of inflation, supply chain, and tight labor will reduce the rate of growth for nonresidential construction in 2022, rather than pulling the volume lower than in 2021.

Data on the fourth quarter and full year of 2021 began rolling out to the public as January ended. The picture painted of the economy by the data is one of extraordinary recovery in 2021; however, the polled consensus of American consumers is less optimistic. With COVID-19 circulating widely across the U.S. during the winter, businesses experienced serious disruptions. Many service businesses were forced to limit hours due to staff shortages caused by illness and resignation. The Census Bureau reported that the number of people not working due to illness reached an all-time high. Inflation soared for groceries, gasoline, and rent. Home prices appreciated by more than 15 percent again, pleasing homeowners but putting homeownership out of reach for many. These kitchen table concerns were exacerbated by partisan politics and media narratives.

The data on the economy tells a different story. Employment grew by 6.4 million jobs in 2021, pushing unemployment to 3.9 percent. That was the unemployment rate at the end of 2018. The number of unemployment claims fell precipitously throughout 2021, dipping below 200,000 per week in December and remaining in the low 200,000s in early 2022, roughly the same level as in early 2020. The number of jobs open began to fall in late January but remained well above 10 million openings. That is four million more openings than unemployed persons. The total number of persons receiving unemployment insurance compensation in January 2022 was 100,000 lower than in January 2019.

Hiring in December and January was consistent with the 12-month average, adding 510,000 and 467,000 jobs respectively. The uptick in hiring reduced the gap in the number of unemployed in January compared to February 2020 to 800,000. An unexpected jump in the workforce participation nudged unemployment up slightly in January to 4.0 percent, but unemployment seems to be a small factor in the current state of the U.S. economy. The Census Bureau’s monthly jobs report, the Employment Situation Summary, has long been viewed as a barometer on hiring; however, it has become clear that the number of people employed has been limited less by slower job creation than by an insufficient number of applicants.

There is a growing disparity between participation rates among the prime workforce cohort (aged 25-54 years) and older workers. Participation for those 55 and older has fallen significantly after a spike when lockdowns ended in May 2020. Whether due to earlier retirements or fear of returning to work, the 55 and older cohort has been shrinking, about 800,000 workers fewer than in 2020. That runs counter to the long-term trends of growing workforce participation among older Americans. Combined with a decline in women in the workforce of about 1.5 million, the decline in workers aged 55 or older suggests that the U.S. economy may be looking at a secular shift to fewer workers.

Whether or not such a shift is imminent, a continuation of this trend through 2022 will limit the growth of the economy. Through most of the two-year pandemic, it has been assumed that the hardest-hit sectors of the economy – like hospitality, travel, and leisure – would see a surge in hiring after the public health concerns faded. Metrics like workforce participation rates and the “quits” rate suggest that restaurants, hotels, retail, and other industries with similar profiles may struggle to find workers. Many restaurants and bars, for example, were forced to maintain limited open hours in 2021 because of staffing shortages, not local mandates.

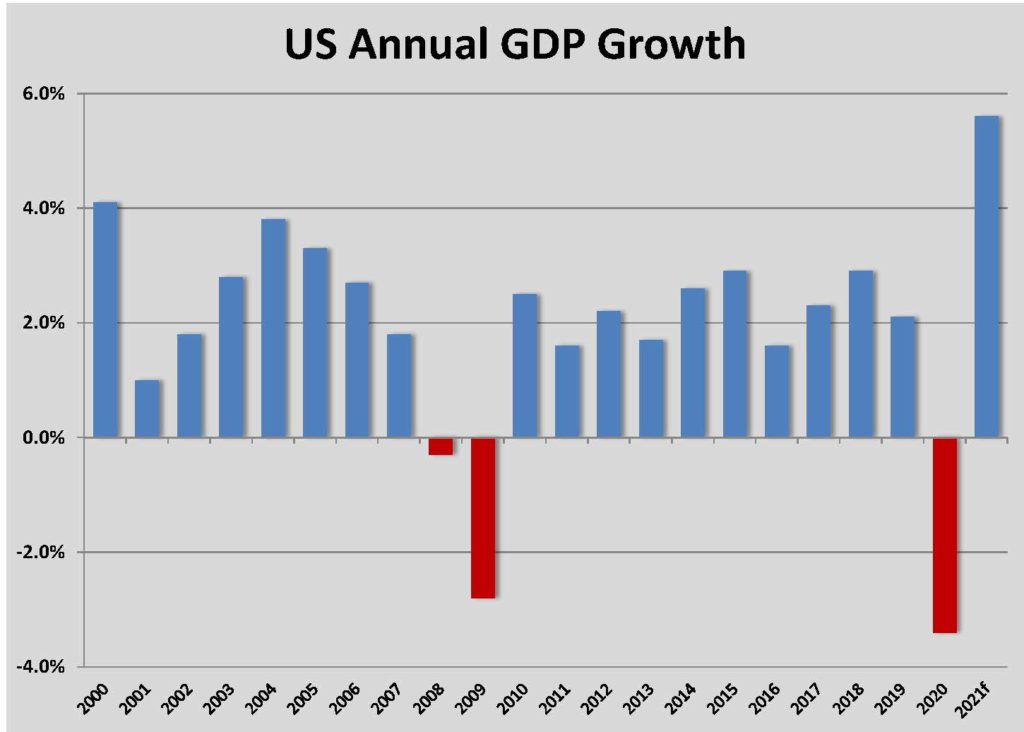

The stresses on service businesses to maintain staffing had an impact on gross domestic product (GDP) growth during the fourth quarter. The first estimates of GDP growth showed that consumer expenditures on services outstripped goods purchases, but the pace of service spending slowed from the third quarter. Consumer spending remained strong overall, pushing GDP growth in the last quarter of 2021 to 6.9 percent on an annual basis. GDP grew by 5.7 percent for the full year compared to 2020. The biggest driver of growth in the fourth quarter was from inventory investment, which made up 70 percent of the growth. Companies rebuilt stock as the year ended after exhausting inventories to manage the ongoing supply chain disruption.

Household incomes and savings declined from the third to the fourth quarter (although still at high levels) as extended unemployment compensation ended.

Net exports contributed to GDP growth instead of subtracting for the first time since the pandemic began in the second quarter of 2020.

Government investment subtracted from GDP growth because of the decline in unemployment compensation, state and local education investment, and federal defense spending.

The U.S. economy is positioned to grow above the long-term trend line again in 2022. Even absent population growth, demand from higher levels of employment and the higher levels of saving, coupled with forecasted higher global demand, should push GDP growth above three percent. That is somewhat lower than was forecasted six months ago; however, accelerated growth in 2021 and the assumption that inflation and higher interest rates will dampen global growth have muted the expectations.

Multiple threats have emerged as the economic threat posed by COVID-19 appears to be retreating. Inflation, particularly extended upward pressure on wages, could cut consumer spending significantly and increases the likelihood of deferrals of construction projects. Disruptions to the supply chain are not being resolved as quickly as hoped. Should the supply chain not improve in 2022, project delays will increase. Implementation of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will require design and bidding that will push realization of the increased spending into the latter part of 2022. And labor shortages will remain an underlying drag on productivity throughout the industry.

It is worth noting that the massive disruption caused by COVID-19 began as the global economy was slowing, possibly approaching recession. The strong recovery in 2021 came despite the threats posed by the pandemic, in part because the economy had begun to slow in 2019. The new threats left in the wake of the pandemic – high inflation, supply chain disruption, and declining workforce participation – will almost certainly keep construction activity from meeting demand in 2022. To the degree that less construction helps rein in those threats, that might be a good thing.