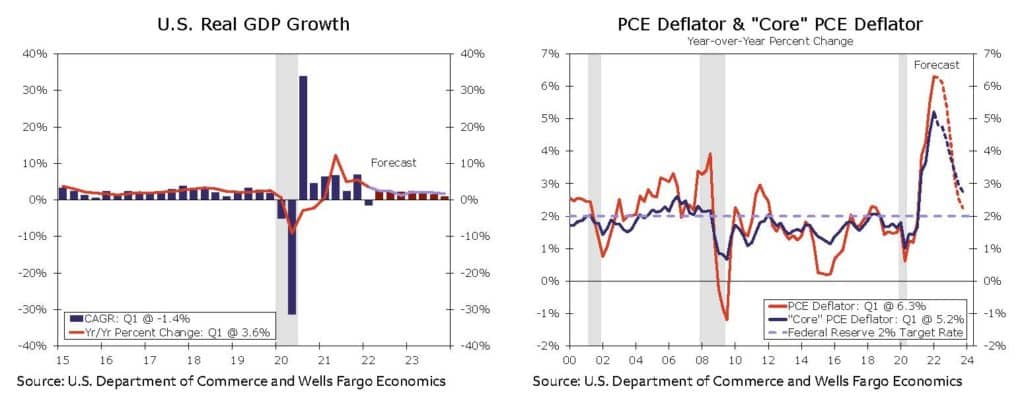

The second reading of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) for the first quarter confirmed that the pace of economic growth is slowing more quickly than expected. The 1.5 percent decline in GDP, in tandem with rising rates and persistent inflation, is bringing rapid revisions by economists and financial institutions to forecasts that were made at Christmas. The pace of these revisions, and the wide range of forecasted outcomes, is an indication of how uncertain the prospects for the U.S. economy are for the next two years.

An examination of the GDP numbers reveals more stability than the headline suggests. Part of the decline in quarter one was the reaction to the unusual inventory building during the fourth quarter of 2021. The lean inventory build combined with a surge in net imports in the first quarter to reduce GDP growth by a staggering four percentage points. The rates of growth for consumer spending, business investment, and residential investment were all above the long-term trend. Payroll employment grew by 1.7 million in the first quarter and industrial production grew at a 7.6 percent annualized rate.

It is unlikely, however, that the pace of consumer spending and residential investment will continue for the balance of 2022. Inflation has already begun to erode spending. Higher costs for construction have curtailed home remodeling and additions, and rising home prices are slowing home purchases. In fact, almost all forecasts for GDP growth in 2022 show residential investment as a negative.

Because of the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan provisions, principally the Paycheck Protection Plan (PPP), businesses continue to be in a strong position. Demand has returned for most industries. The cash boost provided by PPP in 2020 and 2021 is available to be deployed and is expected to drive an increase in business investment of five percent or more in 2022.

For the final three quarters of 2022, the disparity in inventories and import/exports should be less pronounced (although supply chain woes could slow inventory rebuilding throughout the year). At the same time, the waning benefits of accommodative fiscal and monetary policy will cool demand. Expectations for GDP growth in 2022, for which there was a consensus of growth above three percent at the beginning of the year, have moderated dramatically. The Blue Chip Economic Indicators consensus forecasts of economists and analysts expect GDP growth to fall to 1.6 percent for the full year.

Much of the difference in opinion about the outlook reflects the broad variance in expectations about interest rates and inflation. Firms like Wells Fargo Securities and Deutsche Bank see the Federal Reserve Bank staying the course on hikes, pushing the Fed Funds rate well above neutral by early 2023. That scenario makes recession likely. Observers that account for the Fed’s sensitivity to a soft landing see greater potential for a pause in hikes – as happened in 2016 – that reduces the chance of a recession, or at least one that produces a significant increase in unemployment.

Federal Reserve Bank Chair Jerome Powell was more assertive in his comments following the 75-basis point June rate hike, seeming to want to assure markets that the goal was a 2.5 percent neutral rate. Powell did not eliminate the chance of a 75-basis point hike in future meetings, but his comments left that possibility should inflation continue to be high through the summer. Both short-term and long-term rates eased a bit after Powell’s comments, suggesting that investors had begun to price higher rates into their forecasts.

The comments were not upbeat, however, and Powell was also explicit in signaling that inflation was the Fed’s highest priority. He noted that “neutral” was a range, not an absolute rate, and he was clear that the central bank would consider pushing into restrictive territory to cool inflation in 2023. The 75-basis point hike in June should be followed by 50-to75 basis point hikes in July and September. That would leave room for 25-basis point hikes in November or December, depending on the conditions.

Aside from the impact on the economy, the Fed’s actions are important to the construction industry in several ways. The most obvious is the increased cost of borrowing. Lenders’ appetites will decrease, and spreads will go up. For commercial real estate developers, that adds further pressure to pro forma at a time when construction costs are escalating rapidly. It is likely that a significant share of commercial projects will be deferred in the coming year. The April Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey revealed little change in appetite, demand, or lending conditions among either small or large lenders. Anecdotal evidence suggests that will change significantly in June, with conditions tightening.

Lenders are reacting to the volatility and uncertainty, rather than to a material change in the economy. Prior to Christmas 2021, few observers expected the Fed to start hiking rates at all in 2022. The 10-year Treasury rate was 1.5 percent. Six months later, the 10-year has topped the three percent level and the FOMC could well push the Fed Funds rate to three percent this year. When conditions change that much, that quickly (and they rarely do), lenders stop answering their phones.

As rates go up there will be increased difficulty for corporations to borrow and to refinance existing debt. That will depress capital spending. And the thinning of the Fed balance sheet will put pressure on long-term rates, as lower demand for bonds – including mortgage-backed securities – drives prices down and interest rates up. That makes it more difficult for long-term borrowers, like public authorities, to finance major capital projects.

The pace of core inflation did flatten in April and May for consumer prices, but the surge in oil and food prices pushed the consumer price index (CPI) to a 40-year high of 8.6 percent year-over-year. Producer prices were 1.8 percentage points higher than the CPI. That represented the third consecutive month of slowing and suggests that the supply chain may be improving.

If in tandem with the Fed’s restrictive actions, the American consumer and business owner begin to trim spending in anticipation of a recession, the central bank’s policy shifts will be compounded. It is becoming more likely that inflation will remain high unless there is the pumping of the brakes by both the Fed and the markets. After a few months of the new interest rate environment, there are signs of a reaction similar to braking:

- The University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index dipped below 60 in March, a 10-year low. Falling sentiment tends to lead consumer spending, which makes up two-thirds of GDP.

- China’s continued “Zero-COVID” policy pinched growth in the world’s second-largest economy and caused a severe credit contraction in the first quarter, which is expected to push China to ease monetary policy.

- European Union has likely fallen into recession during the second quarter of 2022.

- The Port of Los Angeles reported that the number of ships waiting to anchor in Los Angeles or Long Beach had fallen from more than 100 in January/February to 39 in mid-May.

- The Buying Conditions Index portion of the Michigan consumer sentiment research has fallen below the April 2020 pandemic lows for automobiles, homes, and large household durable goods.

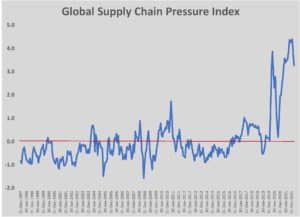

- Two technical measures of supply chain disruption, the Manheim Use Vehicle Index and the Fed’s Global Supply Chain Index (GSCPI), both peaked in January 2022 and have been falling since.

Each of these indicators point to a shift from supply to demand as the driver of economic stress. Clearly, the GSCPI has room to go before the pressures on the supply chain – higher costs, backlogs, long lead times, and low stocks – ease enough to return to the conditions that prevailed since the late 1990s. Slowing demand, however, should accelerate the easing of supply stresses. If consumer behavior does follow sentiment, demand should fall further than expected by mid-summer. Should that happen, supply chains will normalize more quickly than expected.

Quick response by the markets is likely to bring inflation back in line with long-term expectations earlier than forecasted, but probably at the cost of at least a mild recession. That, in turn, would put pressure on the Fed to halt rate increases and slow reduction of its balance sheet, efforts that are needed to return to more normal monetary policy.

Data from the Census Bureau on employment continued to reflect a tight labor market. The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey for May showed 11.4 million openings, nearly double the number of unemployed persons. The most recent Employment Situation Summary – the monthly jobs report – showed hiring was continuing at an accelerated pace, despite challenges in finding workers. Employers added 390,000 jobs in May, pushed mainly by seasonal hiring in leisure and entertainment, professional and business services, government, and warehousing. Construction employment grew by 36,000 workers after no gains in April. The June 1 ADP Payrolls Report, which saw private employers add 128,000 workers in May, is the lone metric suggesting that hiring may be slowing.

Unemployment in May remained at 3.6 percent and the number of unemployed persons was six million, roughly 300,000 more than just prior to the pandemic. The number of long-term unemployed (those out of work for 27 weeks or more) fell slightly to 1.4 million, which was 235,000 more than in February 2020. Both the labor force participation rate and the population-to-workforce ratio remained unchanged in May, with both metrics 1.1 percent lower than in February 2020. Those lower rates have been consistent, suggesting that most of the 1.6 million fewer workers in the labor force are not returning.

Construction spending, not adjusted for inflation, reached an annual rate of $1.74 trillion in April, an increase of 0.2 percent from the March rate and 12.3 percent higher than in April 2021. Private residential construction spending rose 0.9 percent from March and 18.4 percent from April 2021. Private nonresidential construction spending declined 0.2 percent month-to-month but was 10.1 percent higher than in April 2021. Public construction spending was 1.8 percent higher year-over-year.

Economists cited the continuing tight labor supply as a constraint on higher construction activity. There were 494,000 construction jobs open in April, a 40 percent increase from April 2021. The number of open positions exceeded the number of new jobs, suggesting that employers could have doubled the number of hires during the month.

Rising borrowing costs were blamed for the sudden steep reversal in housing starts in May. New home construction slumped 14.4 percent in May from April. Permits for new housing units topped 1.8 million in April, following a surprising uptick in starts in March. Single-family starts were 1.05 million, with multi-family starts falling to 498,000 units. Sales of new homes plunged significantly in April, the fourth consecutive month of declines. Declining sales reflect concerns about rising mortgage rates and reflect a further decrease in affordability. The median price of a new home jumped 19.6 percent compared to April 2021.

The drop in new home sales pushed inventories higher, despite the slump in May, with a nine-month supply of new construction available for sale in May. Combined with the high level of starts, this increase in supply may mark the first signs of cooling for the overheated housing market.

One metric for construction, the AIA’s Architectural Billings Index, remains curiously positive. Unlike most measures of the market, ABI is a forward-looking indicator. The index is a result of a binary survey, which asks if a firm’s billings were higher or lower than the previous month. The April ABI was down from March, from 58 to 56.5, but still at a high level. While the April reading was topped four times in the months following the rollout of vaccines in 2021, no other month had as high a share of firms with billings gains in either the Trump or Obama administrations.

The significance of this high reading is the reliability of the ABI for forecasting construction nine months to a year in advance. The April reading seems to validate anecdotal evidence that owners in many sectors of the construction industry were forging ahead with projects in spite of inflation, or choosing to have them re-designed to fit the current pricing environment. While it could be that continued inflation will halt the projects being designed now, the fact that design is still at high levels six months into double-digit construction inflation is encouraging.

By Labor Day, there should be greater clarity about the major driving economic factors. Fed Funds rate should be at two percent, with another potential increase to come in September. Inflation should be falling if the economy cools and supply chains are normalizing. None of those are certain bets, of course. There are other economic concerns. China’s economy is unlikely to grow more than five percent and could be somewhat lower if COVID-19 remains a regional problem there. The global economy will be slower overall. Global weakness and higher rates will further strengthen the U.S. dollar, making it more difficult for U.S. companies to export. More clarity is unlikely to mean a more favorable view.