When the data on July’s consumer and producer price inflation was announced, the decline in the rate of inflation was evidence that the Federal Reserve Bank’s monetary tightening was working. The cooling of price increases came on the heels of an aggressive 75-basis point hike in the Fed Funds rate in July, meaning that the impact of the hawkish move had not been measured yet. For commercial real estate, which had seen deals dwindle during the second quarter, the good reports offered the possibility that activity would rebound before the end of 2022.

By mid-September, however, those hopes faded when inflation heated up again slightly, and Fed Chair Jerome Powell signaled that beating inflation was the central bank’s top priority, regardless of whether that battle produced a recession. At the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) meetings that followed on September 20-21, the Fed put another 75-basis point hike in place, and Fed officials made it clear in their comments that rates would remain at restrictive levels through 2023.

Most of the headlines about rates have focused on the chilling effect on residential mortgages and home buying. While the near doubling of mortgage rates has dampened the housing market, commercial real estate has been buffeted by the increased cost of capital, the inflation of construction costs, and – more importantly – the growing uncertainty about when conditions will stabilize.

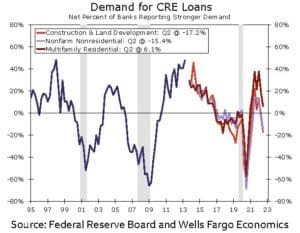

It is the latter concern that has chilled commercial real estate activity. The economy has not necessarily dampened demand for commercial real estate. Other than the market for office properties, commercial real estate is still enjoying the growth in demand that followed the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines in mid-2021. Developers will complain about higher interest rates and cap rates, or higher construction costs, but history has shown that they can adapt to most conditions. To do so, however, developers must know what the rules of the game are. Until the Fed pauses or responds to an economic signal, the rules of commercial real estate finance remain fuzzy. Uncertainty is not a friend to either borrower or lender.

“I agree we can underwrite to any environment, but we do have to have less volatility,” says Robert Powderly, executive vice president at FNB Corporation. “The demand will be constrained until we have some certainty about rates and inflation. The banks are challenged to underwrite to the unknown. They will look at the worst-case scenario as the stress of the project underwriting. Banks are underwriting to a 6.0 or 6.5 percent rate – and it may not end there – based upon the projection of the Fed rate hikes.”

“Most lenders that I talk to are having trouble making deals pencil because they are required to ‘stress’ the underwriting of the property with higher interest rates in the future,” agrees Tyler Noland, chief operating officer for PenTrust Real Estate Advisory Service. “Stressing a property’s performance with higher rates is standard, but the true difficulty is when the future of interest rates is so potentially volatile that you have to apply overly high rate projections into the financial model to be conservative.”

Noland suggests that focusing on the path of interest rates and Federal Reserve policy is “looking at the tail rather than the dog.” He cautions that the determining factor in the current development cycle will be inflation and its effect on the overall economy, noting that Fed policy will react to inflation until it is under control.

Noland also points to the difficulty of forecasting capitalization rates for exiting a construction loan or selling a property when rates and costs are rising unpredictably. The cap rate is a calculation that divides a property’s net operating income by its purchase price. Cap rates offer a standardized metric for buyers and sellers to evaluate properties to judge the yield or return on investment. Cap rates have been several points lower than historical norms since the end of the Great Recession, which ushered in a decade of near-zero rates. Lower cap rates mean higher prices for sellers. Now that rates are rising, so are cap rates, making it harder for lenders and borrowers to reconcile the future value of a property for which future income will be squeezed by higher interest rates.

“At this point, projecting one year out is almost impossible. Projecting five years or 10 years out is completely impossible,” Noland says. “You just have to rely on historical norms and justify that, in the long-term, the world will return to normal. That depends on how you want to define normal.”

Nick Matt, senior managing director and co-head Pittsburgh office of JLL Capital Markets, observes that sellers would prefer to live in the 2010s environment, but lenders have already moved on. Noting that cash-on-cash returns are still paramount to investors, Matt sees a disconnect between buyers and sellers that have not adjusted to the current environment. He says the gap has pushed buyers to the sidelines waiting for clarity.

“Our investment sale brokers were telling us there was supposed to be a large number of deals hit the market right after Labor Day. That hasn’t happened,” reports Matt. “There is too much uncertainty and buyer pools have shrunk considerably. How can a buyer calculate a cash-on-cash return and deliver it?”

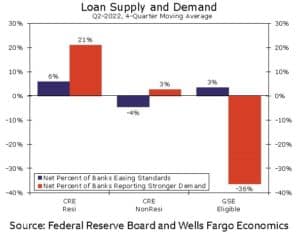

There seems to be widespread recognition that the volatility will dampen the appetite for commercial real estate. Regulators appear to be quietly responding to the market, applying the lessons learned in 2008 about the systemic damage that can occur. Dan Puntil, senior vice president and office manager for Grandbridge Real Estate Capital’s Pittsburgh office, says that there were reports from the National Multi-Housing Council annual conference that top tier of banks – Wells Fargo, JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and their peers – had been told to slow lending, although not because of fears of overexposure to commercial real estate. The same expectation has since been communicated to the next tier of banks.

|

|

There does appear to be a difference in how the national lenders are experiencing the turbulent conditions compared to regional banks.

“Obviously our stress rates have increased quite a bit when we’re looking at a property. The level of activity has slowed down slightly but has not come to a grinding halt by any stretch,” says Lori Soles, vice president, investment real estate for Somerset Trust. “Developers are more cautious, of course, but we are still busy. We are fixing the rate up front when we can. I am looking at refinancing deals coming out of construction trying to lock in before rates increase again. I haven’t received any new construction deals.”

Greg Sipos, executive vice president of corporate banking for First Commonwealth Bank, agrees that market conditions are less than ideal but says that the deal flow is still robust. Sipos expressed concerns about the market that go beyond those of inflation and higher rates.

“The undesirable nature of both hospitality and office are concerns. Banks remain unwilling to lend into these two segments, although hospitality is showing strong signs of recovery,” Sipos says. As a result, banks are full of multi-family. Big banks are having to hit the brakes due to regulatory issues and the smaller banks do not have the balance sheet. There is a lack of cheap capital for banks due to the decline in deposits of the past two years. This will push spreads as well as rising rates.”

Sipos reports that First Commonwealth still has more construction loan requests, but demand for permanent financing exists as well. He says the difference between the expectation of rates during the near term compared to long-term expectations has had an impact on what clients are seeking.

“Clients would rather do some short-term bridge financing floating for three to five years, rather that fix into a longer-term rate with the fed projecting that the increase could be short term,” Sipos says.

The disconnection between short-term and long-term rates makes development financing more expensive, another factor that is an incentive to wait. Loans for development and construction activities are based upon short-term, floating rates, which are in the process of converting to a Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) as a basis. After the September rate hike, markets have been pricing SOFR at four percent and higher through 2023. That compares to just over one-half percent in January 2022. Moreover, uncertainty has made lenders and investors more cautious and, therefore, spreads have crept higher. Borrowers are likely looking at SOFR plus two percent (or 6.5 percent) for floating rates until markets settle.

The change in market sentiment in September is important because the next FOMC meetings will not occur until November, which will give more time for reaction and for inflation to cool. It was the commentary of the FOMC members that sealed the market reaction, especially the dot plot of expectations that showed that 18 of 19 members expected the Fed Funds rate to settle in above four percent through 2023. It is worth noting, however, that in January 2022 few of these same members expected a rate hike in 2022.

There is an element of good news that uncertainty has cooled off the appetite of buyers, sellers, and lenders. There have been times in the past few decades when enthusiasm got the better of common sense and caution. Commercial real estate thrives on doing deals, but sometimes the best deal is the one not made. Current conditions are unfavorable but will pass. Those who are exercising caution today will be the ones positioned to take advantage when conditions improve again.

“The world has changed drastically in a very short period of time,” says Matt. “That said, the market will adjust – and maybe it already has – and all the players will need to adjust accordingly.”